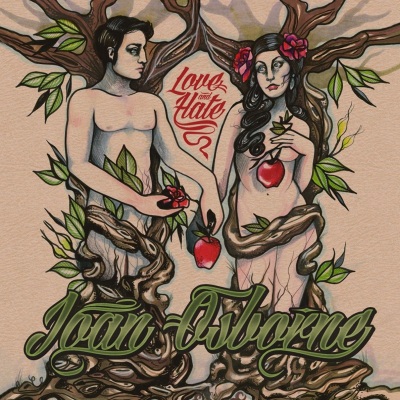

Love and Hate

After nine previous albums that span musical terrains including mainstream pop, blues, throwback soul, rock, and modern country, singer and songwriter Joan Osborne delivers her first formal “song cycle” on Love and Hate. Co-produced once more with Jack Petruzzelli, these songs (all written or co-written by the artist), with their first-person protagonist, traverse the many stages between the poles reflected in the title — though thankfully they never quite reach the latter. This record is ultimately a showcase for the songwriter more than it is the singer, one trying to come to grips with mastering this aspect of her craft. In set opener “Where We Start,” Osborne is clearly influenced by Van Morrison‘s trademark weave of jazz and R&B. Its soulful melodic repetition is underscored by a Veedon Fleece-esque string chart, and well-placed use of a Rhodes piano. “Mongrels” and “Kitten’s Got Claws” are fine rockers that feature Nels Cline‘s stinging guitar playing and a female backing chorus that includes Amy Helm, Gail Ann Dorsey, and Catherine Russell, while “Keep It Underground,” co-written with Gary Lucas, features the same lineup in a funkier, grittier R&B setting. First single “Thirsty for My Tears” comes close to what passes for contemporary country — but much is far less slick. “Not Too Well Acquainted” is soulful, jazzy pop that simultaneously recalls Dusty Springfield‘s kaleidoscopic Philly period and Burt Bacharach‘s mid-’70s era, with gorgeous string and horn charts. Some of these songs falter. The direct melodic quote from Pink Floyd‘s “Us and Them” in the opening phrase of the title track is the best part of an otherwise mediocre tune. An attempt at lushly orchestrated gospel-tinged soul in “Train” is too limited melodically to overcome its arrangements.”Work on Me” and “Secret Room” use Spanish flamenco and fado-inspired frameworks far too lazily to make them work. The tender yet erotic “Raga” places Petruzzelli‘s banjo and hand percussion (not tablas) in a mix with acoustic guitars, harmonium, and Cline‘s lap steel. It simultaneously and successfully juxtaposes East Indian and American folk traditions and closes it all on a high note. Lyrically, Osborne misses at times; she can be too obvious with her metaphors, and use age-old clichéd lines from music history or rhymes that feel stretched to fit. However, these songs are poignant; they present love’s many gradations — its victories, difficulties, and failures — in a sincere context. Love and Hate is uneven, but is worthwhile for the sheer pleasure and authority in hearing Osborne deliver songs from one of the heart’s messiest places.