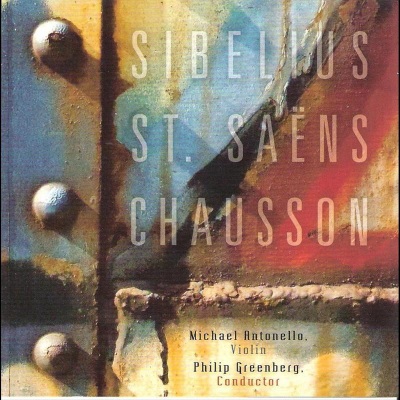

Sibelius, St. Saens, Chausson

Jean Sibelius: Violin Concerto This is Sibelius’s only concerto. “A polonaise for polar bears” was English musicologist Donald Tovey’s impression of the third movement. Sibelius did write other shorter works for violin and orchestra, including 6 Humoreques. An early and enthusiastic proponent of the concerto was violinist Jascha Heifetz, who made the first recording. Sibelius loved the changing of the seasons in Finland, reveling in such simple natural wonders as the arrival of geese on lake ice. His first movement begins in just such a highly restrained manner, as if to describe a frozen, silent landscape. Sibelius’s love for the isolated, windswept coldness of the north seems reflected in the long, lonely violin cadenzas of the first movement. This love of the north is something he had in common with the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, for whom Toronto was too southern a location for comfort. The orchestral violin ostinato seems hardly to start the piece at all, as if one had begun in the middle, emerging from hibernation. The violin enters with a ghostly motive without any sense of meter, like a lone wolf howling over a wintry, windy, frigid landscape, as if exhausted after a long winter of dusky darkness. When Heifetz visited Sibelius, who, unusual for a composer, lived in the country instead of the city, he remarked on how austere the area was and how bone-chillingly cold. Fog lingered over the woods and lakes near Sibelius’s house. Heifetz decided that this first impression, seeing the environs of Sibelius’s house, even before he’d met the composer, was essential for forming his interpretation of the concerto. The concerto is conceived on a grand scale, reflecting Sibelius’s feeling of being a revolutionary for Finnish nationalistic sentiment. Johan Julius Christian Sibelius was brought up in a Swedish-speaking family in Hämeenlinna, part of the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland. In his student years he took on the French form of his name, “Jean.” His parents sent him to a “Fennoman” school, which encouraged the nationalist movement in Finland, throwing off the Swedish language and ties to German culture, and simultaneously the ties to Russia, which viewed Finnish as a mere peasant language. Sibelius wanted to become a standard-bearer for incipient Finnish nationalism, at least in music, just as Verdi had become for a united Italy. ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Camille Saint-Saëns: Violin Concerto no. 3 The French composer, Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) was an only child, brought up by his mother and an elderly aunt after his father died. The two doting women lavished him with attention; his great aunt, who had been highly precocious in music herself, tried to keep up with the traditions of pre-revolutionnary France, at least in manners and dress, and influenced him to look backwards more than forwards, historically, for his cultural inspiration. He absorbed from her a great interest in the Mozartean époque. It must have given her great joy when he surpassed Mozart as a musical prodigy. By age three he had already made the decision to become a composer rather than a pianist. He was already writing down waltzes and galops (a 2/4 form of the waltz, popular in Paris in the 1820s), which he had to give to his aunt to play, because his infant fingers were too stubby. At age 5 he wrote out a 12-bar song in pencil, which his aunt copied over in ink. The father of the singer for whom it was intended was so enchanted, that he gave Saint-Säens the present for which he remained the most grateful for the rest of his life. It was the full score to Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni. When Saint-Saëns finished studying it, two years later, he knew everything he needed to know about orchestration, and had thoroughly incorporated the clean, clear elegant style of Mozart, which would always remain the strongest influence in his own compositions. Saint-Saëns writes about receiving the score at age five: “When I think about it, the gift of such a present to a five-year-old child seems a particularly rash action…yet never can there have been a happier inspiration. Every day, with that miraculous ease of assimilation which is the dominant faculty of childhood, I immersed myself in Don Giovanni and almost unconsciously I imbibed its music, broke myself into score reading, and became acquainted with the different voices and instruments…” Saint-Saëns was so entranced with Mozart’s methods—simple ideas put together to produce masterpieces in combination—that he used them all his life, including in the third violin concerto. “When you study the score [Don Giovanni] closely, how unremarkable are the means employed! Do all these marvels amount to nothing more than simple intervals of an octave, a few bars’ repetition in the bass of a very obvious rhythm, syncopations (which everyone uses), a little figure on the fourth string of the second violins, and those scales, those ‘terrifying scales’ which are so restrained and never go beyond an octave? It is true that these details seem of little or no account in themselves. Their value rises out of their placing, reciprocal harmony, contrasts, and overall balance. In these lie the style, the secret of genius.” The simplicity and clarity of Mozart remained Saint-Saëns’s muse all his life, as opposed to the music of Wagner, which was the principal influence of all other, late-nineteenth-century composers. Though the musical styles of Europe that Saint-Saëns was exposed to changed radically during his long life, from Mendelssohn to Stravinsky, not to mention the political changes in France, from a monarchy to a republic, his own style changed little. While he was the first major composer to write for a motion picture, he was considered highly old-fashioned at the end, not that this is of any consequence today. The concerto is dedicated to the Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908), for whom Saint-Saëns wrote his most successful violin piece, Introduction and Rondo Capricioso, also recorded by Antonello. The concerto, especially the final movement, is highly operatic in style, just as much of Mozart’s music is. Ernest Chausson: Poème Chausson could not be more the opposite of Saint-Säens in terms of the speed of his musical development. He began composing late in life, only to have his life cut short when he ran his bicycle into a brick wall. Chausson himself did not compose a single work until he was 22 and only decided to pursue composition more seriously after hearing a performance of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde at age 24. Just as César Franck wrote his greatest violin work for the Belgian violinist Eugene Ysuae, so did Chausson write Poème. Raised in a well-to-do family, Chausson attained a law degree under pressure from his father, but wealth from his family allowed him to turn to composing, and he chose as his teachers both Massenet and César Franck. In his later years, he also built up a large art collection, and entertained in his home French painters such as Manet, Renoir, Degas, Rodin, as well the poet, Mallarmé (whose words were used by Debussy in many songs), as well French composers such as Satie and Chabrier. Chausson also assisted Debussy in his career. Performers such as pianist Alfred Cortot and violinist Eugene Ysäye performed at his salon, and also the singer and composer Pauline Viardot, for whom the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev (1818-1883) developed a crush which kept him often in Paris. The one-movement, superlatively intense and passionate Poème was inspired by a short story by Turgenev, The Song of Triumphant Love, about two men, best friends, who, tragically, fall in love with the same woman. Although the Poéme is a fantasy, without relation to any traditional classic structure, its rise and fall in tension and the overall melancholy mood suggest it certainly could be a description of a drama based on tragic love. Chausson might also have thought of it as the piece performed during the climactic scene. In Turgenev’s story, the girl, Valeria, cannot decide which one she loves better, so lets her mother choose. The mother chooses the painter over the musician, Muzzio, and, rejected, he sells all his possessions in order to travel to exotic lands, not to return until his broken heart has healed. Five years later, Muzzio returns, showing up on the married couple’s doorstep, to recount amazing stories of his lengthy travels but in no way showing any trace of his former love for Valeria. Then Muzzio picks up his violin, from India. Turgenev writes: a passionate melody poured out…such fire, such triumphant bliss glowed and burned in this melody, that [the couple] felt wrung to the heart and tears came into their eyes; while Muzzio, his head pressed to the violin, his cheeks pale, his eyebrows drawn together into a single straight line, seemed still more concentrated and solemn…When he finished, refusing all entreaties to repeat the song…he pushed his hands into Valeria’s palm and looked so insistently into her face that she felt her cheeks suddenly burning. The story goes on to show Valeria struggling against being rebewitched by Muzzio, and her husband unaccountably losing his ability to paint his wife’s beautiful face. The irresistible passions evoked by the violin playing, which seem to enslave even the violin player himself, have turned everyone’s lives topsy-turvy. Notes by Peter Arnstein